Local Plan Review 2026-2043 Issues and Options Consultation

How Should New Allocations Be Identified?

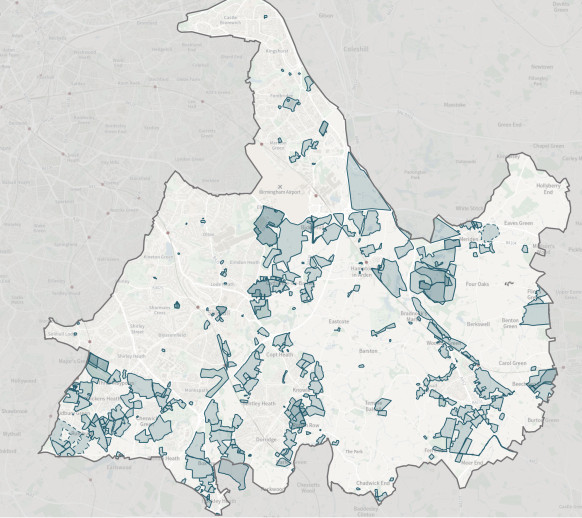

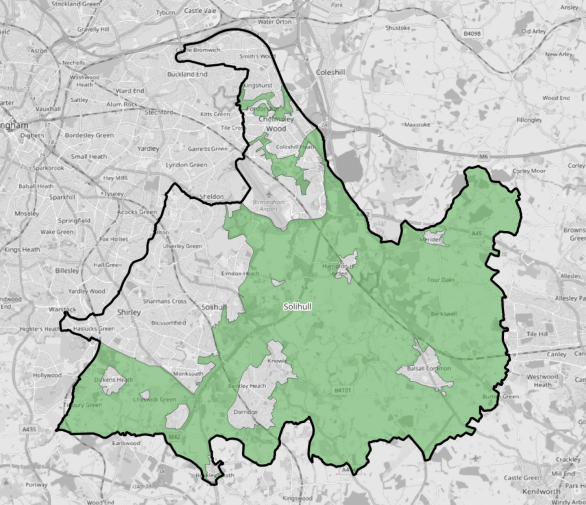

- The Call-for-Sites exercise undertaken in winter 2024/25 resulted in over 300 sites being put forward as being available. As noted at the time, just because a site was promoted through this exercise does not mean that it is a suitable site, particularly as most submissions related to land in the Green Belt. An interactive map and schedule of sites submitted was published soon after the exercise closed. The map extract below shows those submitted across the Borough as a whole[28].

- Around 300 sites were promoted with housing as a preferred land use and these amounted to an overall area of 2,381 ha, with an average size of 7.93 ha[29]. Using the estimated capacities provided by the promotors, this totals 54,309 dwellings. It should be stressed that these estimates have not been tested, nor should it be taken that the sites are suitable and/or deliverable.

Site Typologies

- The following paragraphs look at some of the advantages and disadvantages of different site typologies being used to contribute towards the land supply.

New Settlement (5,000 plus dwellings)

- Alongside changes to national policy, the government have also consulted on and identified a range of new town options. Only one of these is identified within the wider West Midlands, but it introduces a concept of creating new settlements to help meet housing needs.

- The creation of a new settlement has not previously been considered within the Local Plan Spatial Strategy. It is acknowledged that it would likely require significant infrastructure investment, and its location would need to be carefully considered having regard to existing landscape character, Green Belt implications and infrastructure capacity. Options may exist though and in planning terms a new settlement could include a sizeable expansion of an existing hamlet for example to form a new village. The Council are aware that similar approaches have been taken in South Warwickshire for example.

- It is important to note that any new settlement would not be a ‘silver bullet’ to meet the remaining housing requirement as only a limited number of dwellings would be delivered in the plan period[30]. However, similar in a way to Arden Cross and the NEC it could provide a longer-term housing land supply option that extends beyond the plan period.

15. Should the spatial strategy be amended to accommodate at least 1 new settlement? If so, where could this settlement be located and how many homes could it deliver in the plan period? Comment

Large, Infrastructure Led Development (500 plus dwellings)

- Infrastructure led development in the context of the Council’s Local Plan can be characterised by identifying what infrastructure may be required in an area and using this to help determines where residential development could then take place in order to support the delivery of the infrastructure as part of the development itself.

- For instance, as an illustration, if development were to be directed towards the edge of a settlement then as part of an ‘infrastructure led development’ the proposals could include provision for the principal vehicle access serving the development to be provided in the form of a road linking two key radial routes into the settlement thus avoiding additional traffic having to move through the centre of the settlement. However, the development would need direct and convenient routes for pedestrians and cyclists to access the centre of the settlement. An illustration of this is how the principal access to the Barratt’s Farm development would be provided as an ‘outer’ route that connects Station Road to Wate Lane.

- This type of development would normally be expected to occur on the edge of the urban area or adjacent to rural settlements that are well served by facilities, such as the Borough’s rural towns, i.e. Balsall Common and Knowle, Dorridge & Bentley Heath.

- Similar to the new settlement option, the lead in time needed to plan for such developments generally means they deliver few dwellings early in the plan period, but unlike that option they do generally get completed by the end of the plan period.

Medium Sized Sites (50 – 500 dwellings)

- This type of development could be accommodated in similar locations as that for the larger infrastructure led developments noted above but could also be accommodated in some of the smaller rural settlements too. This would be dependent upon being located in a sustainable location which is explored in a later chapter.

- Whilst developments of this size, particularly towards the lower end of the scale, are unlikely to generate the need for large scale infrastructure to support them coming forward, they will have infrastructure needs that occur as a result of a number of cumulative developments occurring in an area. For instance, improvements to education facilities. This is also explored in a later chapter.

- Delivery on sites of this size often occurs relatively quickly so that they can make an immediate contribution towards land supply, at least in part.

Small Sites (10 – 50 dwellings)

- This form of development can occur in most settlements that are able to provide basic levels of services. They can occur as infill developments, or ‘rounding off’ of an existing pattern of development.

- Like the previous example, they are unlikely to need to be supported by large scale infrastructure, but their cumulative impact will need to be taken into account.

- Being smaller developments means that they can be completed much quicker than the larger sites such that they are likely to play an important part in making sure there is a supply of land immediately available.

A Balance of Typologies

- The emerging plan is likely to require a balance of sites to be included as allocations to ensure that upon adoption of the plan the Council is able to demonstrate a five-year land supply for new housing. Due to the lead in times for larger developments this will mean that a number of smaller sites will be needed.

17. What are your views on the emerging plan including a balance of site typologies? What are the advantages and/or disadvantages of incorporating large, medium or small sites in the land supply? Comment

- Evidence submitted during the examination of the 2020[32] included delivery rates (i.e. the number of new dwellings built per year) on the sites to be allocated, and this generally fell into three types of sites:

- Large sites of over 500 dwellings that would be capable of supporting multiple housebuilders – 70 to 90 dwellings per annum would be built at these sites.

- Small sites of less than 500 that are generally built out by a single housebuilder – 50 dwellings per annum.

- Specialised developments (for instance at sites like the NEC) that can include a greater range of housing products that could be marketed towards traditional house builders and the buy-to-rent market[33] – 100 – 120 dwellings per annum.

18. Are the delivery rates outlined above reasonable assumptions to be used in calculating a housing trajectory over the course of a plan? Comment

Principles Relating to Potential Allocations

- When considering how the spatial strategy should be updated, it is useful to explore some principles that could be taken into account. These include the following:

- Sustainable Locations.

- Green Belt Impacts (including cumulative effects).

- Protecting Vulnerable Gaps.

- Protecting Rural Services.

Sustainable Locations

- Promoting sustainable transport has a number of components to it, including:

- Locating development in sustainable locations.

- Ensuring there is safe and suitable access to developments for all users.

- Any significant impacts from the development in terms of capacity and congestion can be mitigated to an acceptable degree.

- In this respect the NPPF advocates the use of a ‘vision-led’ approach. Through the emerging Local Plan, the Council can set out what its vision is for delivering well-design, sustainable and popular places.

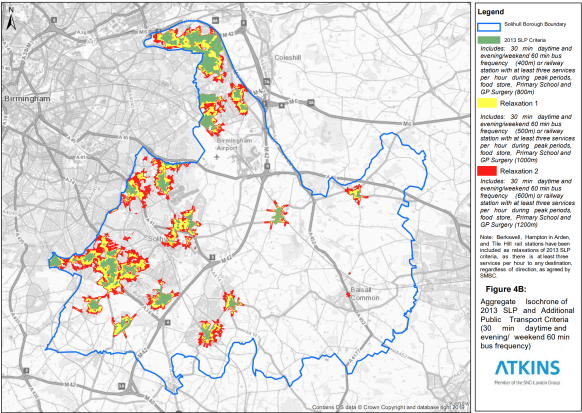

- Under the current Local Plan, policy P7 (Accessibility and Ease of Access), residential development should be:

- Within 800m walk distance of a primary school, doctor’s surgery and food shop selling fresh food.

- Within 400m walk distance of a bus stop with a high frequency bus service providing access to employment opportunities and retail facilities; and/or within 800m walk distance of a rail station providing high frequency services.

- The accessibility work[34] undertaken for the 2020 plan assessed which parts of the Borough met the criteria in Policy P7 of the 2013 plan and tested how accessibility varied where relaxations to the criteria were to be made. This was illustrated as follows:

- It is interesting to note how Inspectors have used the 2013 policy, and two examples are provided below with the Inspectors comments and conclusions on accessibility being reproduced.

- The first example relates to an appeal for 95 dwellings on land at 722 Kenilworth Road, Balsall Common[35]. Here the Inspectors comments on accessibility were as follows:

Local Plan Policy P7, requires that development meets specified accessibility criteria unless justified by local circumstances. In particular, development should be within specified distances of services including a primary school, doctors’ surgery, shops, a bus stop and rail station both of which should have high frequency services.

The submitted Transport Assessment sets out that the required distances to schools and a bus stop are met, although Councillor Burrow on behalf of local residents sets out greater distances to these facilities. It is clear however that the distance from the site to a number of the local facilities is greater than specified in the policy. In addition, bus and rail services do not meet the specifications for a high frequency service set out in the policy.

Nonetheless, the proposed development would be no further from the facilities in the village than existing dwellings both on Albany Lane and to the east of Kenilworth Road. There are footpaths and pedestrian crossing facilities from the site access northwards into the village which would allow access to facilities on foot, albeit at some distance. Furthermore, the development proposes improvements to local walking measures in the form of a pedestrian crossing on Kenilworth Road to the north of the site.

Bus services are available from the village to Solihull and Coventry with two services per hour. The nearest bus stop is on Kelsey Lane which is within walking distance of the site. The nearest railway station is around 2.2Km to the north with train services to Birmingham, London and Northampton.

A Travel Plan is also proposed which aims to reduce vehicular trips and encourage the use of more sustainable modes of transport. In the longer term the Package, to which the development will contribute, is also to include active travel measures including improved cycling and walking infrastructure on Kenilworth Road.

Having regard to the above factors, and to the housing land supply situation addressed in greater detail below, I am satisfied that in this case, local circumstances would justify allowing development in a location which is further away than recommended from the facilities in the village. In this context, I agree with the Council that there would be no conflict with Policy P7.

- The second example relates to an appeal for 2 dwellings on land south of Destiny Cottage, Friday Lane, Catherine-de-Barnes[36]. Here the Inspectors comments on accessibility were as follows:

Catherine de Barnes is the nearest settlement with services and facilities. The shop in the village, albeit not a large food store, would be less than 800m walk from the appeal site and would, therefore, comply with the distance requirement of the first bullet point of Policy P7a) of the LP. However, the policy seeks to ensure that housing development is within the indicated distances of all of the services and facilities listed, so as to provide a sustainable location.

Although the proposed site would be within 800m of a small shop I have no compelling evidence that it would be within 800m of a school, doctor’s surgery, or rail station. It is also further than 400m to the nearest bus stop. The development of the appeal site for housing would, therefore, be contrary to Policy P7.

Moreover, the walk would be along a country lane where the wide grass verge, which is provided outside the existing houses, narrows significantly between the housing and the village. There are no pavements and no street lighting. Albeit that the walk would be on fairly level ground, the journey would be likely to take more than 10 minutes. It is unlikely that residents of the development would walk between the site and the nearby settlement for day-to-day facilities and unlikely that the residents would walk to Catherine de Barnes to catch a bus to facilities in other settlements. Cycling would be a reasonable option for travel between the site and the larger settlement, though residents are unlikely to cycle for shopping trips.

Given the location of the site, beyond the settlement, there are limited opportunities for sustainable transport modes or for residents to undertake many activities without the use of the private car. In my judgement, the occupants of the future development would be likely to rely on the private car for the majority of journeys. Even if the occupants had low emissions vehicles, as suggested by the appellant, the scheme would not promote sustainable modes of transport.

Furthermore, I have no compelling evidence that the development of the 95 dwellings, nearer to Catherine de Barnes, would improve the public transport or pedestrian linkages of the appeal site.

Policy P7 sets an exception for proposals of fewer than three dwellings in urban areas west of the M42 and in rural settlements. I have already found that the site is not within a rural settlement, it is also not within an urban area. Therefore, this exception would not apply.

There is nothing within Policy P7 that limits it to major developments or even suggests that the policy seeks to target major developments, as the appellant asserts. The wording of the Policy refers to all new development, thereby encompassing even single plots. The aim of the policy is to provide development in areas with access to services and facilities and to encourage a shift to sustainable forms of travel. I have, therefore, given full weight to Policy P7 and the appeal proposal fails to comply with the requirements of the policy.

I do not have the full details of the other developments referred to by the appellant or whether they were justified by the circumstances of each scheme, as is accepted as exception to the requirements of Policy P7 of the LP. Nevertheless, I have considered the appeal before me based on the submitted evidence.

For the above reasons, I find that the site is not a suitable location for housing, having regard to the accessibility of services and facilities and would be contrary to Policies P5 and P7 of the LP which, taken together, seek to resist new housing in locations where accessibility to employment, centres, and a range of services and facilities is poor, and seek to ensure that all development is focused in the most accessible locations through meeting the accessibility criteria listed, unless justified by local circumstances.

- From these examples it seems that although the proximity to services envisaged by Policy P7 isn’t always met, what Inspectors have been keen to ensure is that pedestrian access to the nearest settlement can be made along safe and convenient routes.

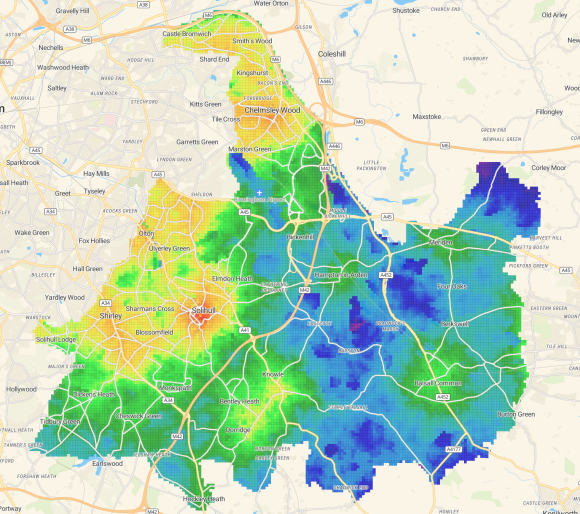

- The Department for Transport have been working on producing a connectivity tool[37]. This displays how any location in England and Wales is connected to everyday services by walking, cycling and public transport, but this does risk over simplifying what is a more complex situation. An example map for the Borough from this tool is as follows. This shows connectivity in Solihull within a national context:

- This is a useful example to help illustrate how accessible (to services) all parts of the Borough are, or aren’t, as the case may be. Of course, this, and the Council’s own 2020 accessibility work, measured current circumstances, and through development proposals, some locations can be made more accessible, e.g. by providing facilities within the development or improving public transport accessibility to the site.

- Linking potential developments to existing active travel networks can also assist in improving the accessibility of sites. This would align with existing and anticipated strategies/plans, for instance:

- Solihull Connected and/or the forthcoming West Midlands Local Transport Plan 5. The West Midlands LTP5 seeks to achieve 6 Big Moves and includes a focus on Accessible and Inclusive Places. This means careful planning of development with accessibility in mind and improving sustainable transport to allow people to access opportunities without needing a car.

- The Cycling and Walking Strategy[38] (2021) is another such example, and this can be incorporated into the Council’s vision-led approach to promoting sustainable transport – i.e. seeking new developments to link up with the Borough’s cycling & walking network. The latest guidance for new cycling infrastructure should be considered on top of this, including the Department for Transport’s LTN1/20 Guidance.

19. What should the Council include in its vision-led approach to promoting sustainable transport? Comment

- One factor to consider is the travel patterns and car movements that will take place from development sites, and evidence will be prepared to help inform such choices. This could include influencing where around a settlement development should take place. For instance, if there’s evidence that traffic from the Council’s rural towns will tend to move in a northwest direction (i.e. towards Solihull and/or UK Central), should that development be located on the northwest side of the settlement? This would be instead of to the southeast of the settlement with the result that vehicles would have to travel through the centre of the settlement.

20. Should development be focused on the northwest of the Borough’s rural towns, even if this means that more vulnerable Green Belt land may have to be released? Comment

Railway Stations

- Proximity of potential developments to railway stations is expected to become a focus of further national planning reforms following a recent joint announcement[39] by the Housing Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer. It indicates that:

“Housebuilding near well-connected train stations will receive a default “yes” in future if they meet certain rules, ensuring more high-quality, affordable homes are built in and around our key towns and cities, saving commuters time and boosting access to housing.

Planning reforms to give greater certainty and strength for development around well-connected rail stations, including trains and trams, will be proposed through a new pro-growth and rules-based National Planning Policy Framework, which will be consulted on later this year.

Recognising the significant benefits for jobs and growth that can be unlocked by building around train stations, these rules will extend to land within the Green Belt, continuing efforts to ensure that a designation designed in the middle of the last century is updated to work today.”

- This has now been incorporated into policy S5 (Principle of development outside settlement) and policy GB7 (Development which is not inappropriate in the Green Belt) in the draft NPPF (2025). Regardless of whether there is unmet housing need or not, development would not be inappropriate if it meets these criteria:

- be within reasonable walking distance of a railway station capable of providing a high level of connectivity to services and employment;

- be physically well-related to a railway station or a settlement within which the station is located;

- be of a scale which can be accommodated taking into account the existing or proposed availability of infrastructure;

- not prejudice any proposals for long-term comprehensive development in the same location;

- in the case of major development, comply with policy GB8 (the Golden Rules).

- be within reasonable walking distance of a railway station capable of providing a high level of connectivity to services and employment;

- This is likely to mean that the Council will need to consider what scope there is for developments around the rural rail stations in, or close to, the Borough, including the following locations:

- Berkswell

- Dorridge

- Earlswood

- Hampton in Arden

- Tile Hill

- Whitlock’s End

- Widney Manor

- Wythall

- Under the draft NPPF, the expectation is that densities of development around railway stations that are ‘well connected’ should be 50 dpa.

- Although the draft NPPF does not specify what a reasonable walking distance is, a distance of 800m is often used in such circumstances[40]. In terms of frequency of service, the draft NPPF does provide the following:

“Well-connected rail stations … which, in the normal weekday timetable, are served (or have a reasonable prospect of being served due to planned upgrades or through agreement with the rail operator) throughout the daytime by four trains or trams per hour overall, or two trains per hour in any one direction.”

21. Is 800m an appropriate measure to use to define a ‘reasonable walking distance’ of a railway station, if so why do you believe so, or if not why not and what alternative would you suggest? Comment

Protecting Rural Services

- New development can often make an important contribution towards rural services that may be in decline or are otherwise vulnerable to being lost through lack of a population to keep the services viable.

- One example of this principle is in relation to Temple Balsall school which has suffered falling pupil numbers and has a limited local population to draw pupils from. The call-for-sites exercise has indicated that development opportunities are available nearby[41], and whilst this location may not be as accessible as others, it could have the benefit of enabling a valuable local service to be sustained. This could also include benefits in supporting public transport through the settlement and potential links to Berkswell station.

22. Should the Spatial Strategy in the new plan take into account the benefit developments can have to make rural services viable, even if they are located in less accessible locations? Comment

Green Belt Impacts (including cumulative effects).

- The concept of Green Belts has been a feature of national planning policy since the 1950’s and its fundamentals have remained pretty constant, including:

- The importance of openness and permanence.

- Green Belt serving five purposes[42].

- Changes to Green Belt boundaries only in exceptional circumstances.

- Planning permission being granted for development in Green Belts only in very special circumstances.

- As described in paragraph 16, one of the main changes to Green Belt policy is the introduction of Grey Belt sites. And national policy does mean that where it is necessary to release Green Belt land for development plans should prioritise Grey Belt before other Green Belt locations[43].

- The Council has therefore commissioned Arup to produce a fresh Green Belt Assessment (GBA) that will be produced in accordance with the updated Green Belt policy in the NPPF and follows the national Planning Practice Guidance on Green Belts that was updated in February 2025. This GBA will replace that produced by Atkins in 2016 that was used to inform the 2020 plan. The Arup assessment will be published in due course[44].

- The NPPF advice includes the following[45]:

“Exceptional circumstances in this context include, but are not limited to, instances where an authority cannot meet its identified need for homes, commercial or other development through other means. If that is the case, authorities should review Green Belt boundaries in accordance with the policies in this Framework and propose alterations to meet these needs in full, unless the review provides clear evidence that doing so would fundamentally undermine the purposes (taken together) of the remaining Green Belt, when considered across the area of the plan.”

- The NPPG gives some further guidance as follows:

“Considering the impact on the remaining Green Belt in the plan area.

How can the impact of releasing or development on the remaining Green Belt in the plan area be assessed?

A Green Belt assessment should also consider the extent to which release or development of Green Belt land (including but not limited to grey belt land) would fundamentally undermine the purposes (taken together) of the remaining Green Belt across the plan area as whole.

In reaching this judgement, authorities should consider whether, or the extent to which, the release or development of Green Belt Land would affect the ability of all the remaining Green Belt across the area of the plan from serving all five of the Green Belt purposes in a meaningful way.”

- Given the changes to the NPPF, the emerging SDS and the need for local plans to be reviewed every 5 years, this does create tensions with ensuring that only the minimum Green Belt release occurs (to address needs) with the desire to maintain one of the acknowledged characteristics of Green Belts being their permanence.

- This does allow, through the plan-making process, the cumulative effects of significant Green Belt land release to be taken into account. This consultation gives an opportunity for stakeholders to indicate how the Local Plan should take this NPPF and NPPG advice into account.

23. What factors should the Council take into account when assessing whether its approach to Green Belt land release would fundamentally undermine the purposes (taken together) of the remaining Green Belt, when considered across the area of the plan?

Maintaining the Openness of Green Belt for Other Reasons

- National policy takes quite a narrow view on the importance of Green Belts (for the 5 purposes noted above46), but it is important to recognise that land designated as Green Belt also provides other benefits to being kept open. This is recognised is one of the guiding principles for the SDS (set out earlier) that states:

Enhancing the functions of green spaces - the SDS must recognise the strategic importance of green open spaces in the West Midlands and establish a consistent and positive approach to Green Belt land beyond the principal planning purposes of preventing urban sprawl and the merging of towns. The SDS should seek to enhance the wider functions of green open spaces ,including giving priority to i) protecting and enhancing natural habitats and promoting biodiversity, ii) enabling access to recreational land, iii) protecting and establishing carbon-sequestering land uses, and iv) recognising that successful growth and the promotion of the region requires these spaces.

- Through this consultation, the Council is keen to hear views on how this can be achieved.

24. The Green Belt has potential to provide other benefits that extend beyond the 5 purposes of including land in the Green Belt. What do you believe these additional benefits could be and what evidence do you believe there is, or there could be, to support this approach? Comment

Protecting Vulnerable Gaps

- Whilst Green Belt policy has preventing towns from merging as one of its five purposes, the Council is keen to explore whether this fully reflects the disposition of all of the Borough’s rural settlements, or whether further policy is required, and if so whether there is evidence to justify this approach.

- The Borough’s smaller rural settlements have a sense of identity and character that sets them apart from their neighbours which are often located in a different parish, yet the physical gaps between the settlements can be quite narrow and vulnerable to development that could see them merge into one amorphous conglomeration that would result in the loss of identity and character.

- This is particularly the case in the Blythe area (west of the M42 and north of the M40) that accommodates four settlements (Blythe Valley, Dickens Heath, Cheswick Green and Tidbury Green) in close proximity to each other that are separated by short distances[46]. To the east of the M42 there are also vulnerable gaps to the northeast and northwest of Hockley Heath. In other areas the gaps between settlements are larger and less vulnerable.

- A strategic gap policy could be developed that would seek to protect the individual sense of identity and character of these settlements by preventing development in the vulnerable gaps between them. If so, which gaps ought to be protected? As a starting point to consider which gaps, it is useful to set out which settlements were considered through the Solihull Rural Settlement Hierarchy Assessment (2025), namely:

- Balsall Common

- Barston

- Berkswell

- Bickenhill

- Blythe Valley Park

- Catherine-de-Barnes

- Chadwick End

- Cheswick Green

- Dickens Heath

- Eastcote

- Hampton-in-Arden

- Hockley Heath

- Illshaw Heath

- Knowle, Dorridge and Bentley Heath (KDBH)

- Meriden

- Millisons Wood

- Temple Balsall

- Tidbury Green

25. Should the Council develop a Strategic Gap Policy to protect vulnerable gaps between settlements, and if so why (or why not)? Comment

26. What evidence do you believe may justify this approach? Comment

27. If a Strategic Gap Policy were to be developed, which gap or gaps do you believe it should cover and why? Comment

Other Guiding Principles for the Spatial Strategy

28. Should the principles outlined in this chapter be incorporated into the Spatial Strategy, if not, why not, and are there any other principles that should be included? Comment

[28] The submission process allowed those promoting a site to indicate the land uses they believed the site was available for including housing, employment, biodiversity, renewable energy and minerals. The map extract provided here shows all potential uses, not just residential.

[29] There will be some overlapping of proposals and this area would not represent a developable area. Where an estimate of developable area was provided this reduced the area to 2,224 ha.

[30] This is especially the case as no new settlements have been promoted by landowners or a consortium of interested parties, and therefore proposals would need to be put together ‘from scratch’, and with such a long lead in period completions would only occur at the end of the plan period.

[31] A later chapter of this consultation looks at other forms of infrastructure that may be needed, for instance education provision.

[32] For instance document reference SMBC026 – Council’s Updated Housing Land Supply Position and Other Updates.

[33] These often include apartments which get completed and made available for occupation on a block by block basis.

[35] APP/Q4625/W/24/3351230 – 27th February 2025.

[36] APP/Q4625/W/24/3356348 – 9th June 2025.

[38] The strategy outlines the overall strategic approach to active travel in Solihull. The document supports the National Cycling and Walking Plan, adopted in July 2020 and sets a clear standard for cycling and walking infrastructure. It aims to embed cycling and walking initiatives into local policy and ensures major developments consider integrating active travel infrastructure from the start. Alongside the comprehensive new strategy, a Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plan (LCWIP) was also approved.

[39] Housebuilding around train stations will be given default “yes” - GOV.UK – 18th November 2025.

[40] # add source

[41] For instance, site references CFS/24/151 and CFS/24/145 (a capacity of around 140 dwellings).

[42] a) to check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas; b) to prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another; c) to assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment; d) to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns; and e) to assist in urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land.

[43] If brownfield options aren’t sufficient to deliver the level of growth needed.

[44] It is not believed necessary for the GBA to be published alongside this consultation as it will be evidence (not policy) that will support the iteration of a plan that identifies sites for development as part of a preferred option.

[45] Paragraph 146.

[46] This pattern continues further west with settlements in Bromsgrove.